Can you tell in which century a painting was produced by looking at it? In this post, I explain my attempt to get a computer to become proficient at just this task.

I was particularly interested in the area of art because it has long been considered to be a final frontier for computers. We humans have recently gotten used to ceding ground to the machines, but at least art seems like the last bastion of human superiority. Sure, a computer can be made to understand chess, but only because the game’s rigid logic translates well to computer code. We are far less convinced that computers can understand the abstract boundaries and softened edges of fine art. Judging in which century a painting was made, a task that seems fit for an art historian, seems out of the question for a computer. And yet, with modern methods it has become easily achievable.

This is a very high-level primer that is designed to get you thinking about machine learning conceptually. It’s specifically for those who have no technical background, as there is no math or code involved in my explanations. You should come away with a lightly sketched notion of how machines learn, and in particular, how neural networks work.

Let’s begin by surveying the task before us. I’ve downloaded about 300 images of European paintings from the 15th and 17th century and labeled them. Here are some samples below:

Some 15th Century Paintings

Some 17th Century Paintings

What qualities separates these two sets?

It’s not clear cut, but after looking at lots of these painting, a few defining characteristics emerge:

15th Century

- Light, brightly colored

- Lots of gold

- Religious theme

- Lots of Madonna and Child vignettes

- Less realistic imagery

- Medieval clothing

17th Century

- Dark

- Secular theme

- Realistic

- Frilly clothing

- Peasant images

These are just general trends that I noticed in the data, you may have different impressions. Regardless of particulars, it’s critical to be aware that we have just made use of the result of millions of years of evolution. Our highly-developed visual and cognitive systems are miraculously able to perform the sophisticated tasks of seeing objects, observing details, and then abstracting them into rules which we use to organize categories. In this case, separating 15th from 17th century.

Humans have big starting advantages when it comes to image comprehension. To us, an image looks like:

It is effortlessly meaningful. In an instant after looking at this image, we can see that it features an old peasant woman, laughing at something, and holding an impressive beer mug.

Here’s the computer’s eye view of the same image:

[ 94, 79, 74],

[ 92, 77, 72],

[ 89, 74, 69],

.... etc.

[ 40, 39, 44],

[ 40, 38, 39],

[ 41, 37, 36]

How can a computer take this raw input, and observe patterns in a way that meets or surpasses human performance?

How can we teach a computer what Medieval clothing is or what a peasant looks like? How can we write a program that will be able to identify Madonna and Child imagery, or distinguish different painting styles like “realistic” and “impressionistic”? In short, how do we get the computer to recognize the same rules that we see so effortlessly when we see these paintings?

There are two roads before us: either top-down or bottom-up.

Top-Down

This approach involves feeding the computer rules, and then working at translating those rules into something the computer can understand and detect. It’s a top-down philosophy and has the convenience of being simple to conceptualize. We simply take the rules that we see and try to give them to the computer. For example, we can take something we know about what most 17th century images have in common: they are dark. A good rule to separate 17th century paintings from 15th would then be:

If an image is dark, it’s a 17th century image

Translated to something more along the lines of a computer instruction, we might take the average pixel darkness for the entire image and if it is greater than a certain value, say 50, then it’s a 17th century image.

However, we quickly run into problems with 15th century images like this:

This image shows us that our rule is insufficient as the dark clothing of the man in the front, and the overall earthy tint would likely get it incorrectly classified as being 17th century. Let’s amend our rule by requiring 15th century images to be light or contain religious imagery (this painting shows a man in prayer). Leaving aside the major concern that we don’t yet know how to write rules to analyze the “religiousness” of an image, we can say that our new rule is:

If an image is dark and doesn’t contain religious imagery, it’s a 17th century image

Checking through our catalog of images, we unfortunately stumble upon this 17th-century painting:

It’s fairly light-colored, and has religious content (note the wrestling cherubs at the top), yet it’s from the 17th century. This violates our current rules.

Let’s save ourselves some time. We could keep going down this track, applying rules and amending them to account for all of our paintings, but we’d see that rules that cover all cases are nearly impossible to write. Like a blanket that’s too small for the bed when you pull it in one direction, the other side’s occupant gets cold. Perhaps it’s time to look at other solutions.

Bottom-Up

Instead of the first method which requires translating our rules into something a computer can understand, the second approach is much more elegant, if a bit more abstract. It involves giving the computer the images we want to classify and the labels (whether the image is 15th or 17th century) and then having it deduce its own set of rules. We give it the right answers, it just has to figure out how they are right.

The problem of taking pixels and turning them into predictions can be solved using a machine learning algorithm called neural networks. With a neural network approach, our source of inspiration is the human brain.

The brain is made up of cells called neurons. For our purposes, neurons work like little electrical gates. They receive electrical pulses from other neurons or from sense organs, process these input pulses in some way, and based on the results of the processing either fire or don’t fire an electrical pulse to the next neuron which may begin the process all over again. We refer to the particular internal processing they do of the inputs that they receive as the neuron’s “function”.

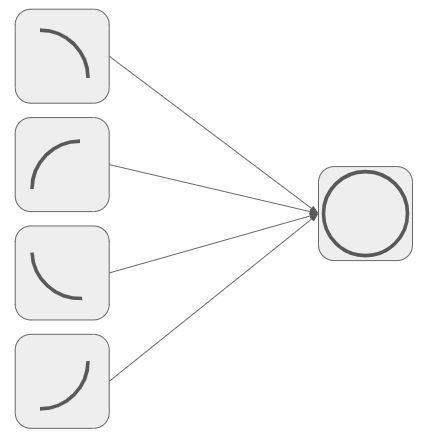

Despite their simplicity, multiple neurons arranged together allow for the potential of complex cognitive functions. For example, take this simple arrangement of five neurons:

The left 4 neurons take a whole bunch of inputs from other neurons or sensory cells, process the inputs in some way, and then fire or don’t fire a signal up to the neuron on the right. Each of these neurons will fire when it detects that a certain portion of the image contains an arc. If all 4 of them fire, the object being perceived from the inputs is a circle.

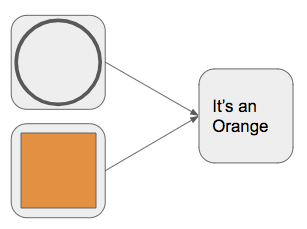

The circle neuron’s output can be channeled to higher-level neurons. Like this:

The circle neuron, when fired together with the orange color neuron, triggers the “It’s an Orange” neuron to fire.

The “It’s an Orange” neuron’s output may feed into an even more abstracted neuron like an “It’s a Fruitbowl” neuron, which might rely on the output from other mini fruit networks to make its decision.

Remember that both the circle neuron and the orange color neuron are based on lots of sensory cells and lower-level neurons feeding their outputs up the chain to the next level of neurons’ inputs. This is exactly what we want to do with our images: take each pixel, and feed it up the chain in the network until it reaches the final node which says: “15th or 17th century”.

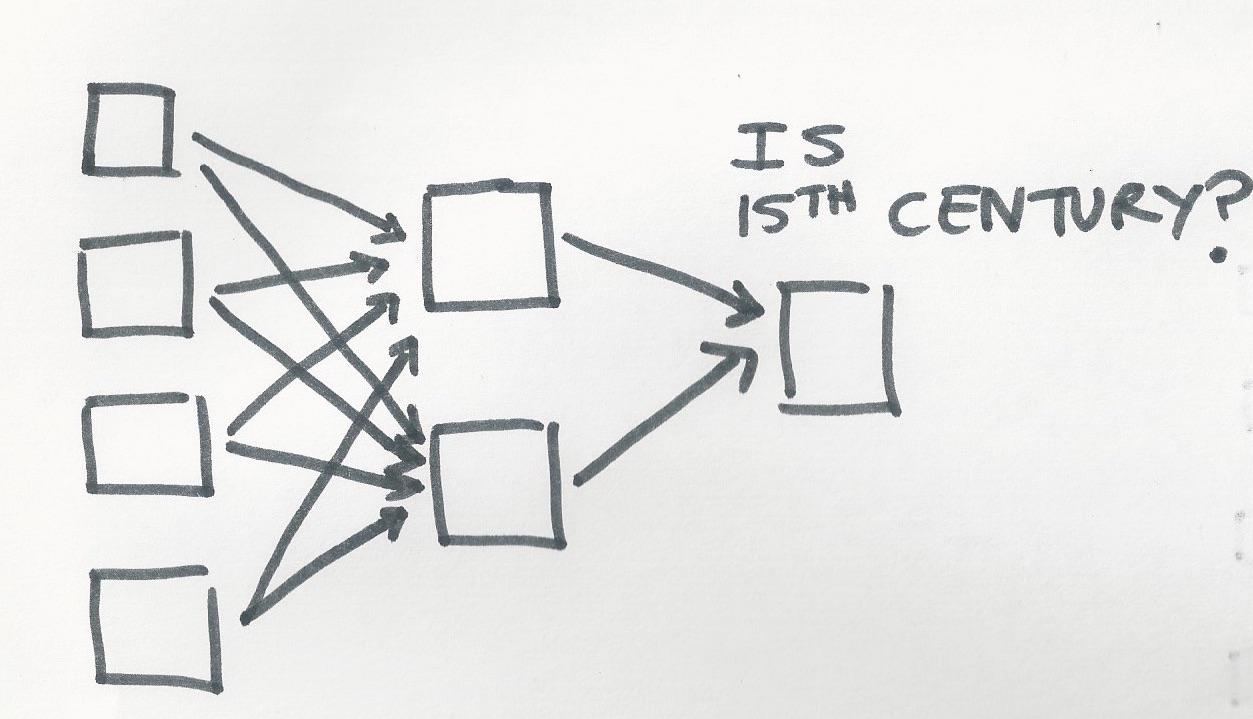

If we were to draw what this network would look like, it would be something like this:

Except much more layers of neurons, and many more neurons in each layer. Note how each neuron feeds into every neuron of the next layer up? This allows every neuron in the network to be able to process from all of the inputs from the image.

Note also how each network in this network is blank, i.e. each neuron has no job yet. This is because we always start from nothing, and then teach the network what each neuron’s function should be. In its current blank state, if we fed pixels into this network, it wouldn’t do anything. The job of the computer is to fill in each of these blanks, ideally in a way that will allow the finished network to make the highest number of correct guesses possible.

To start out, we’d give the computer a list of images with labels. In our case these images would be of paintings, and the labels would be whether or not the painting is from the 15th or 17th century.

With the labels, the computer knows what century each image is supposed to belong to. It can then make a starting random guess what each neuron’s function might be without looking at the label, and see how far off it is (as an average of all of the guesses it makes for each image). Based on the error, it will take a small step in the right direction (figuring out which direction is the correct one to reduce error involves a small amount of calculus) with our next set of guesses and try again, re-evaluating the error from the new batch of guesses. Gradually, it gets closer and closer to guessing all of the proper functions of each of the neurons in the network, to optimally arrive at as many correct painting classifications as possible. That’s the gist of it.

Starting with a blank slate of a certain arbitrary number of blank neurons and layers, it guesses and guesses each of the neuron’s functions until it comes up with the right combination to maximize the number of correct classifications. It’s a process that’s quite a lot like trial and error, though it is slightly more enlightened than that.

The Results

Can we teach a computer to distinguish 15th from 17th century paintings? Yes. In general, a program that follows the outline above, makes far fewer mistakes than you or I might (unless you are an art historian). When examining the results, it’s amazing how startlingly human-like its behavior is. The paintings that we would guess correctly, incorrectly, or be stumped by, the computer guessed similarly. For example, here are its least certain predictions:

The first painting has a bit too much gold compared to the typical 17th century image. The second painting has some aspects of religious imagery (angels flying around), yet it’s a 17th century image in realism, clothing, etc. The third looks like it could be a pious 15th century lady at first blush, but then again it’s got a peasanty and darkly-colored vibe to it. Judging by these examples where the algorithm couldn’t make up its mind, we can see just how human its indecision is. The things it was confused by are also confusing to us. Apparently the algorithm is using a lot of the same rules that we came up with to distinguish these images (and many more that we didn’t think of, or couldn’t perceive). Amazing.

I ran this algorithm on just 300 images which took about 1 human hour to gather and label. Its accuracy was 93%; it was correct in its guess better than 9 times out of 10. This result was produced by a lump of metal and silicon that has no idea what either the 17th or 15th century were, what a peasant, angel, merchant, or monk looks like, and indeed no idea what art is either. Our computer art historian certainly has unusual methods for doing its job, but it also gets great results. I sense the frontier of human superiority eroded just a bit more.